3 Point Parameterization of Affine Transform

Table of Contents

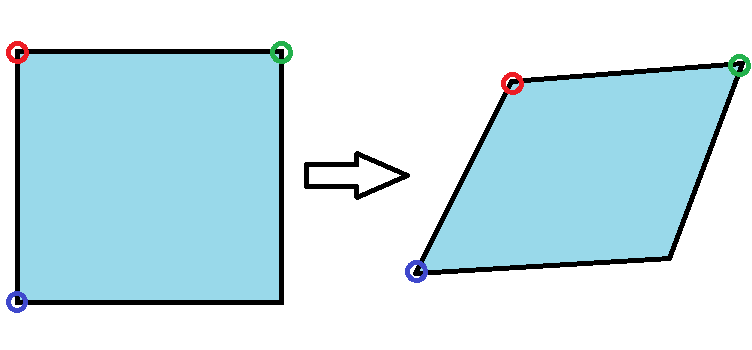

Review on Affine Transforms⌗

1-------------2 1---------2

| | / Result /

| Input Image | ---> / Image /

| | 3---------+

3-------------+

There are many ways to warp an image. Some of the most useful ways:

- Translation: Motion defined by how corner 1 moves.

- Similarity: Motion defined by how corners 1, 2 move.

- Affine: Motion defined by how corners 1, 2, 3 move.

- Homography/Perspective/Projective: Motion defined by how all corners move.

In this article I describe the most beautifully simple way of looking at practical affine transformations, which can be parameterized by looking at where three of the corners are located in the final image.

Rendering an Affine Image Warp⌗

For rendering, the most efficient way to parameterize an affine image warp is using a transform matrix, rather than specifying how the corners are moving. In fact, you have to use the inverse of the transform matrix, because the rasterizer is doing lookups backwards to the source texture.

Each pixel of the output image B needs to do texture lookups from image A, in the backwards direction rather than forwards, to render the output image:

1---------2 1-------------2

/ / | |

/ B / ----> | A |

/ / | |

3---------+ 3-------------+

The textbook affine transform matrix:

[ a b t0 ]

T = [ c d t1 ]

[ 0 0 1 ]

Another way to represent this is R*x + t, which is less ambiguous about the

orientation of the matrix. R is a 2x2 scale and rotation matrix, and t is the 2x1 translation matrix:

[ a b ] [ t0 ]

R = [ ], t = [ ]

[ c d ] [ t1 ]

Irrespective of the type of pixel interpolation method (bilinear, trilinear, bicubic, etc) used to render the warped image, the texture sampler coordinates are calculated as:

ix = R11 * (x + 0.5) + R12 * (y + 0.5) + t0 - 0.5

iy = R21 * (x + 0.5) + R22 * (y + 0.5) + t1 - 0.5

The 0.5 offsets are needed to correctly sample starting from the centers of the pixels rather than from the edges. Note that all the 0.5 factors can be precomputed so they do not need to be done per pixel:

t0' = t0 - 0.5 + 0.5 * (R11 + R12)

t1' = t0 - 0.5 + 0.5 * (R21 + R22)

And then the lookup is more intuitively:

ix = R11 * x + R12 * y + t0

iy = R21 * x + R22 * y + t1

Efficiently Inverting an Affine Transform Matrix⌗

Since the bottom row of the matrix to invert is [0, 0, 1] there is a shortcut:

[ Inv(R) -Inv(R) * t ]

T' = Inv(T) = [ ]

[ 0 1 ]

And since R is a 2x2 matrix, there is a nice closed-form solution for its inverse:

det(R) = ad - bc

[ d -b]

[ ]

[-c a]

R' = Inv(R) = -------------

det(R)

t' = -R' * t

Together this yields:

[ R' t' ]

T' = [ ], which is the affine transform matrix we use for rendering.

[ 0 1 ]

To map a point from B (u, v) to the source point from A (x, y):

x = R11' * u + R12' * v + t0'

y = R21' * u + R22' * v + t1'

Applications for 3 Point Parameterization⌗

Aside from human interactions - where someone using graphics software is trying to draw an affine warp by hand - there are also applications for computer vision.

For image registration (a key step in direct visual odometry, visual trackers, and marker trackers), software attempts to solve for an unknown transform, given two example images.

It is little known that solving directly for the transform matrix has some disadvantages. As explained by “Parameterizing Homographies” (Baker & Kanade, 2006) you get more accurate results by solving for the more intuitive representation using the 3 corner control points. In a bit we’ll show intuitively why that is the case [1*].

The three corner control points are specified by 6 floating point values (3 x, y coordinates), just as there are 6 variables in the matrix.

But when rendering an image warp, how do we go from the 3 control points to the affine transform matrix we need?

Converting from 3 Point -> Matrix⌗

The forward transform from points in A -> points in B can be calculated:

T * A = B -> T = B * Inv(A)

[ x1 x2 x3 ] [ u1 u2 u3 ]

where A = [ y1 y2 y3 ], B = [ v1 v2 v3 ]

[ 1 1 1 ] [ 1 1 1 ] 3x3

[ R11 R12 t0 ]

and T = [ R21 R22 t1 ]

[ 0 0 1 ]

First simplify the problem and assume normalized corner coordinates { (0, 0), (1, 0), (0, 1) }. This makes matrix A mostly zeroes and trivial to invert. Then, multiplying B by A yields the surprisingly simple forward affine transform matrix:

[ u2-u1 u3-u1 u1 ]

T_norm = [ v2-v1 v3-v1 v1 ]

[ 0 0 1 ]

To return to the previous section [1*] we can now see why using this matrix representation intuitively has worse convergence. An optimizer iteratively nudges each of the 6 values based on the local gradient, but when the optimizer tries to adjust one variable independently it is unintentionally also disturbing other control points. Using independent variables for optimization is worth the effort.

By simply multiplying by Diag(1/w, 1/h) we recover the forward affine transform matrix for rectangular images of (w, h) pixels:

[ 1/w 0] [ (u2-u1)/w (u3-u1)/h u1 ]

T = T_norm * [ ] = [ (v2-v1)/w (v3-v1)/h v1 ]

[ 0 1/h] [ 0 0 1 ]

The final elegant result in C++ code:

#include <cmath> // std::abs

struct AffineTransformMatrix {

float R11, R12, t0;

float R21, R22, t1;

bool From3PtParams(

float w, float h, // Size of input image in pixels.

float u1, float v1, // Position of Upper-Left of input image in output image pixels.

float u2, float v2, // Position of Upper-Right of input image in output image pixels.

float u3, float v3) // Position of Lower-Left of input image in output image pixels.

{

// Calculate forward transform if the input image was 1x1.

R11 = u2 - u1; R12 = u3 - u1; t0 = u1;

R21 = v2 - v1; R22 = v3 - v1; t1 = v1;

// If input is invalid:

const float epsilon = 0.00001f;

if (std::abs(w) < epsilon || std::abs(h) < epsilon) {

return false;

}

// Denormalize to actual input image size.

w = 1.f / w;

h = 1.f / h;

R11 *= w; R12 *= h;

R21 *= w; R22 *= h;

return true;

}

inline bool Invert()

{

const float a = R11, b = R12, e = t0;

const float c = R21, d = R22, f = t1;

const float det = a*d - b*c;

const float epsilon = 0.00001f;

if (std::abs(det) < epsilon) {

R11 = 1.f; R12 = 0.f; t0 = 0.f;

R21 = 0.f; R22 = 1.f; t1 = 0.f;

return false;

}

const float inv_det = 1.f / det;

R11 = d*inv_det; R12 = -b*inv_det;

R21 = -c*inv_det; R22 = a*inv_det;

// Calculate t' = -Inv(R) * t

t0 = -(R11*e + R12*f);

t1 = -(R21*e + R22*f);

return true;

}

};

Similarity (2-point) Transform⌗

Representing similarity transform with 2 corners of image:

1-------------2

| | 1-----2

| A | ---> | B |

| | +-----+

+-------------+

Similarity transforms capture changes in translation, rotation, and scale. This is different from Euclidean transforms that cannot represent scale.

When working with global-shutter far-field imagery, similarity transforms are sufficient for characterizing camera frame motion: Panning, zooming, rotation. These can be parameterized by how any 2 corners of the image are moving. We choose the top two corners so that most of the coordinates are zeroes.

But when warping an image, it’s necessary to convert back from the corners representation to the usual 2x3 affine transform matrix because this is the most efficient parameterization of the transform for an image warp.

The forward transform from points in A -> points in B is trival to solve by hand by again choosing normalized corner coordinates (x, y) = { (0, 0), (1, 0) } -> (u, v) = { (u1, u2), (v1, v2) }:

T_norm * (x, y) = (u, v)

[ A B C ]

T_norm = [ -B A D ]

[ 0 0 1 ]

A = u2 - u1

B = v1 - v2

C = u1

D = v1

This expression is equally as elegant as the affine transform version.

By simply multiplying by Diag(1/w, 1/w) we recover the forward transform matrix for rectangular images of width w pixels. Yes, it only depends on the width of the image unlike the affine transform.

[ 1/w 0] [ (u2-u1)/w (v1-v2)/w u1 ]

T = T_norm * [ ] = [ (v2-v1)/w (u2-u1)/w v1 ]

[ 0 1/w] [ 0 0 1 ]

The same code used to render an affine transform can be used to render a similarity transform, without performance penalty.

Extensions⌗

To get the backward transform for e.g. rendering, use the fast matrix inverse method described earlier.

The scaled transform formulas above are the ones to use when computing Jacobians of the transform, meaning that the pixel coordinates end up being normalized from 0..1 in the calculations (e.g. derivative in x direction with respect to u1 is x/w), which improves numerical stability.

And to get the matrix transform between two warped images (A -> B) specified by control points, we can simply combine two transforms:

T_AB = Inv(T_norm(A)) * T_norm(B)

Note that we can pick the “intermediate” rectangular image to be normalized in size, so there is no need to fix the scale.

Is this new?⌗

While these results seem simple, they are also unpublished and uncommon:

These validated results are simpler than any other methods in use today. For example OpenCV is solving a giant 6x6 linear system using generic approaches.

Stack Overflow suggests similarly complex algorithms to compute these transforms.

"A Closed-Form Solution for the Similarity Transformation Parameters of Two Planar Point Sets" (Shamsudin, 2013) suggests a much more complex calculation as well.